Newsletter Archive Mar. 11, 2022

This weekend, brew a cup of darkness with two new-process shu puer from the factory of Chen Keke and Li Dong – Shu Longzhu (Sweet Dragon Ball) 2016 and the Cha Tao (Aged Old Tree) 2017 cake, now back in stock after selling out surprisingly quickly.

When we first started buying muddy black bricks of shu puer tea over 20 years ago, this tea was treated with an air of mystery. Shu puer’s signature ripening or “fermentation” process had been around since 1973, but written knowledge about this process was spotty. Western tea traders hyperbolically called it “a state secret.” Despite this, in our early trips to Yunnan, we were welcomed in by tea makers eager to show off the efficiency and cleanliness of their ripening process. They possessed both pride in what they were doing and an eagerness to keep getting better.

In the years since, there’s been persistent scientific and commercial interest in understanding this process better as puer tea has gone from an obscurity to a luxury investment vehicle and even a health food. Things have come a long way for shu puer ripening, in part, due to the efforts of scientists like Dr. Chen Keke.

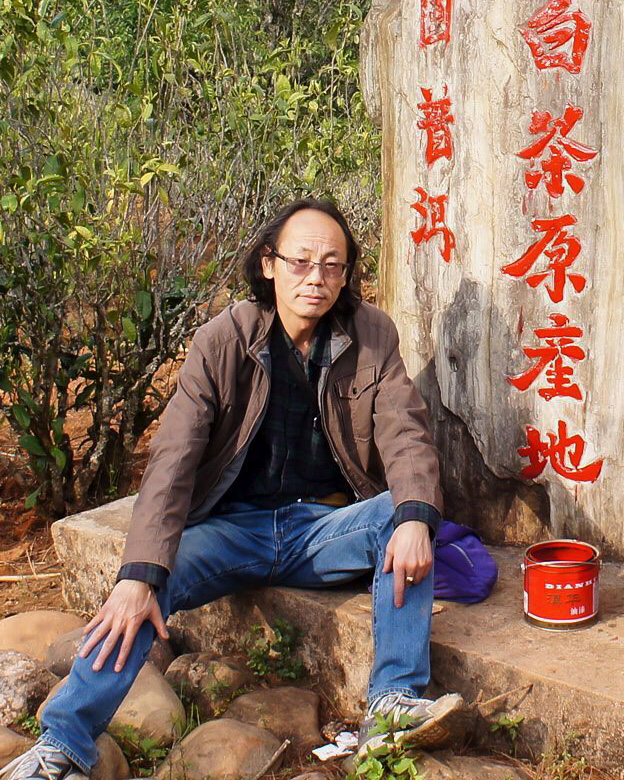

Chen Keke knows his tea but also knows his mushrooms, molds, and microbes. He schooled at the University of Oregon, researching mycelium. One gets the impression that Professor Chen absorbed some of Oregon’s far-out counterculture while he was there, too. Watching him scramble up tea mountains in his leather jacket with a cigarette in his lips and his hair blowing every which way, he looks a bit like Mick Jagger. Austin spent a few weeks driving through Yunnan with Professor Chen back in 2015. When we asked Austin to describe the experience, he only uttered the words, “oh god.”

The rockstar comparison isn’t far-fetched. Professor Chen is well known as a researcher in Yunnan. His post at the Chinese Academy of Science in Kunming has him submerged in the understanding of the microorganisms at work in shu puer processing. His work devises ways to nurture those that give the best flavor and minimize waste in the ripening process, requiring less turning (and less breakage). These techniques make it much less risky to use rare, expensive, or single-origin tea material for making shu puer.

Professor Chen works on further developing his own methods in a custom-built factory located in Youleshan, a sort of experimental laboratory for shu puer ripening. Here maocha sourced from different parts of Yunnan is processed in small batches, using a patented starter of microbes. The careful ripening of forest-harvested leaves for Shu Longzhu and the unusual blending of Camellia taliensis with Camellia sinensis var. assamica leaves in the Cha Tao cake all happened in this facility.

This extremely sophisticated handling of the delicate puer ripening process puts years of experience to the task. Fortunately, we don’t have to be mycologists to appreciate the exquisitely clean and sweet flavor of the tea it produces.