Newsletter Mar. 10, 2023

Are you wulong aficionado? An intrepid newbie? Someone who’s just looking for a decent cup of tea?

This weekend’s feature is for you. We picked six wulong teas to represent the three historic origins of wulong tea in mainland China. These are teas with instant appeal, yet with histories dense enough to geek out on. Get knock-out examples of each, some classic and some modern.

That’s Rougui and Little Red Robe from the Wuyi Mountains, Golden Tieguanyin and Traditional Tieguanyin from Anxi County, and Snow Orchid and Magnolia from Wudong in the Phoenix Mountains.

Sample the six and geek out on the finer points of regional style, or simply stock up on a favorite.

As you can taste, not all wulong is the same – but historical records suggest it descended from a single place. The history is a little controversial, but there’s a lineage here. Read on below to know where wulong tea comes from and where it’s going.

Where is Wulong tea from?

Wulong tea (aka Oolong) is partially oxidized tea, typically roasted, and made from leaves plucked at a relatively mature standard. It’s generally believed that wulong tea, by this description, was invented in northern Fujian Province, gradually developing into a regional style in the Wuyi Mountains by the 18th century.

Wuyi yancha or “rock tea” was the first wulong, mentioned in 1734 by Lu Tingcan (陆廷灿) in his Sequel to the Classic of Tea (续茶经), which is the earliest record of the term, Wuyi Yancha. He included many aspects of Wuyi tea, such as plucking and production practices.

These techniques spread into southern Fujian, taking root in Anxi County and farther south still to Chaozhou on the Fujian-Guangzhou potential border, before finally migrating to Taiwan in the late 19th century.

With each origin, the locals adapted the style to suit each region’s unique tea plants, climate and tastes.

The originator, Wuyi’s rock wulong, generally remains the “darkest” of the styles, with a prominent charcoal roast. The fragrant incense wood, stone fruit, and mineral qualities of classic Wuyi wulong is on full display in Rougui. Meanwhile, Xiao Hong Pao shows a more modern treatment with an emphasis on the style’s floral and lightly caramelized sugar potentials.

Anxi County’s wulong began in a similar style to Wuyishan’s – dark and charcoal roasted with a moderate twisting of the long leaf. You can taste this in Traditional Tieguanyin. But Anxi’s wulong is now more commonly made into vibrant green, less-roasted, lightly oxidized teas with aromas like gardenia and sweet, buttery green artichoke flavors. Golden Tieguanyin is an example par excellence.

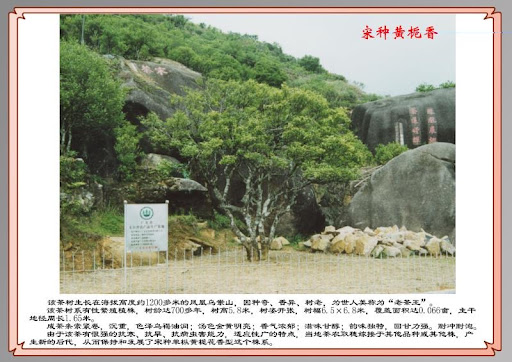

The Dan Cong wulong of the Chaozhou region took the the techniques of Wuyishan and applied them to the utterly distinct tea plants of the origin. Genetically exceptional, the “half-tree-half-bush” plants of the Phoenix Mountains were cultivated for tea production over 600 years ago.

The cultivars of these exceptional trees traditionally get named after their distinct fragrances, like the Yu Lan Xiang (Magnolia) and Mi Lan Xiang (Snow Orchid). Perfumy, complex, fresh floral and terpene aromas meet with a tangy and drying mouthfeel.

Where is wulong going?

Each wulong origin remains proudly distinct, while the influence of each shows on one another. It’s now not uncommon to see Wuyi Wulongs processed with lighter roasting and oxidation – perhaps taking inspiration from the light flavors of Anxi’s tea. Conversely, the success of Wuyi’s black tea seems to have rubbed off on Chaozhou tea makers as they experiment with “full oxidation” treatments of Dancong. Wulong, like it always has, will continue to evolve. This tea’s history is long, but it’s far from complete. We can’t wait to explore what’s next in store along with you.