Newsletter Archive Jul. 30, 2021

Tea making is a complicated art, all the more when we’re talking about famously complex teas like Longjing. Manuals written on Longjing almost always say that it takes 10 particular hand movements to shape this tea during its wok frying. How are these 10 movements learned?

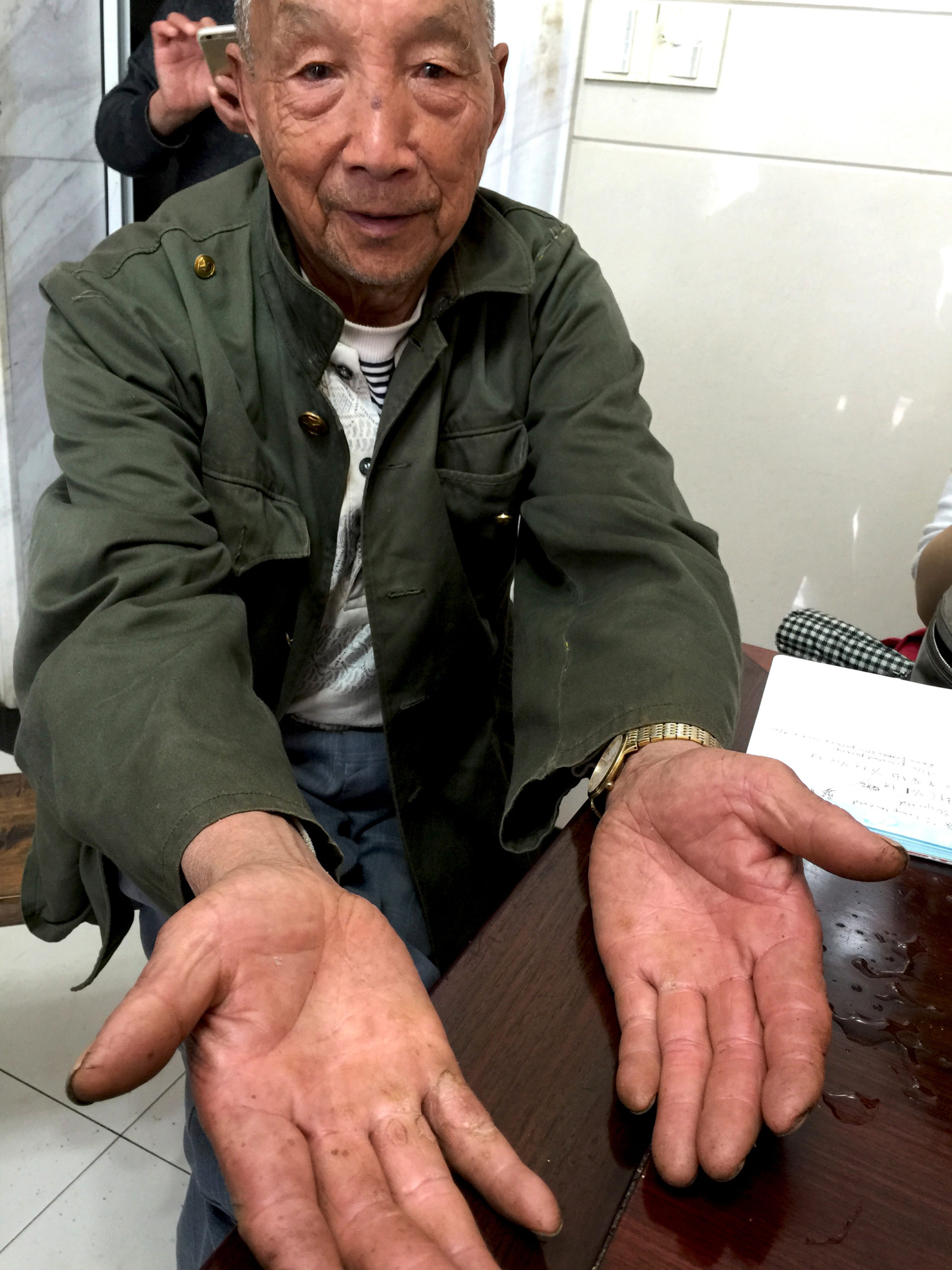

Zhuping once put this question to the late Weng Shangyi, who had made award winning Shifeng Longjing for nearly seven decades and made this tea for us for many years. Mr. Weng answered, “Ten movements? I’ve never heard of that.”

Zhuping figured he just misheard her question. Mr. Weng’s daughter then helped ask again in the old master’s native Zhejiang dialect. Still the question was met with confusion and an insistence that the matter was much more direct. “When I learned how to make Longjing, we just focused on doing two things: make the leaves flat, tight and collected; control the water in the leaf, make sure the leaves don’t feel too heavy and damp but also not too dry and crispy.”

It turns out, the concept of Longjing’s “10 distinct movements” came from the analysis of scholars. For those making the tea, it’s not about distinct movements, but correct results — it’s knowing what tea made with proper technique looks and feels like, and that is the focus of practice, practice and more practice.

By Mr. Weng’s own example, a master has to live in their craft. Like famed cellist Pablo Casals, still practicing his cello four hours a day at the age of 90, the greatest tea makers are the ones practicing their art, forever seeking progress. Seven Cups has always sought out tea makers who are committed to their art, and the quality of the tea they make has always been worth it.

Old-time Longjing drinkers are fond of saying that Longjing’s flavors are at their best in high-summer. After a four-month rest from harvest, the toasty aromas from Longjing’s pan frying are just a little bit softer while the tea’s core flavors are still sweet, vibrant and green. It’s a balance of complexity and easy drinking, an antidote to the heat — a breeze from the spring when we need it most.

2021’s Shifeng Longjing sold exceptionally fast and we’re down to the last few kilograms. The Weng family’s tea is sold out at origin, so be forewarned — more Shifeng Longjing won’t be here until spring 2022.