The tea makers of Huangshan

Green tea maker Wang Huizhou is the son of the legendary Wang Fangsheng, a famous expert in Chinese tea who has shared his knowledge with thousands of tea farmers and producers in Anhui Province. While the Wang family’s Huangshan Maofeng green tea is the legacy product of seven generations of this countryside family, Mr. Wang Fangsheng was also the inventor of the wildly popular blooming teas that open like a flower when infused. As Mr. Wang Jr. tells the story, the painstakingly hand-sewn bundled leaves of this invention were inspired by the velvety density of his mother’s roast corn pancakes. First created in 1986, Mr. Wang senior developed over 600 designs. His blooming tea was even presented as a formal gift by then Chinese President Hu Jintao to Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2007. Within China’s long tradition of gifting tea as a wish of health and prosperity, there are few honors a tea can receive beyond being deemed worthy of being given as an international gift.

As fifth and sixth generation tea makers, respectively, Wang Fangsheng and Wang Huizhou are part of a lineage of tea making that has been maintained through a very difficult stretch of history.

Beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, the tea industry, especially in the eastern provinces such as Anhui, faced multiple cycles of destruction. It started with the Opium Wars that began the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, followed closely by the Tai Ping Rebellion that burned China from the south to the north in a campaign of total war comparable to Sherman’s March To The Sea in American history. The war was one of the bloodiest wars ever fought and during that period the Wang family still made tea.

In the 20th century, decades of tumult from the fall of the Qing, the Japanese Occupation and the Second World War, then followed by the Chinese Civil War, completely wiped out the tea industry. Still, the Wang family of Huangshan continued making tea.

Their practice persisted through the chaos of the Mao era and it continues to the present day. Part of what made that possible was living in a very remote area of Anhui, high up in the Huangshan mountains.

Climbing to the peaks of Huangshan

In the early days of Seven Cups, China’s tea industry was still privatizing after years of a planned economy. Many tea making companies were yet to exist, so rather than look for companies, we looked for isolated tea makers that carried forward traditional tea making. We found them through tea scholars, and Mr. Wang senior was one of the first we found.

Wang Fangsheng was a very cultured man. When we first met him, his courtesy and subtle temperament reminded us of the images of the ancient scholars, men of letters who shared tea in landscape paintings of mountains with clouds floating by pine trees that grew out of craggy cliffs.

The route up to his home village was a long drive up roads so narrow that you could touch the walls of the village buildings they ran between by rolling down your car window. Mr. Wang’s village was at the end of the road, far from Huangshan City. Then, to get to his factory we had to climb a very steep ridge — a serious hike — and then continue along a mountain path for another third of a mile to get to his factory.

The Fangsheng Tea factory is both a feat of careful engineering and painstaking work. Nested into the steep mountainside, just below the mountain’s apex, are two buildings: a two-story factory and a smaller building holding a kitchen and a bunkhouse. They sit on a foundation built of stones. Everything that went into the factory had to be carried up the mountain by hand. The factory is such a far walk up the mountainside that a long cable line had to be installed to quickly transport tea down the mountain as soon as the team finishes making it. It was quite an experience just to sit on the porch there and have a cup of tea.

Although in his later years, Mr. Wang senior no longer made the climb up the mountain every spring, his son Wang Huizhou has continued tea making in his stead.

Strong ties to the local Anhui tea community and industry

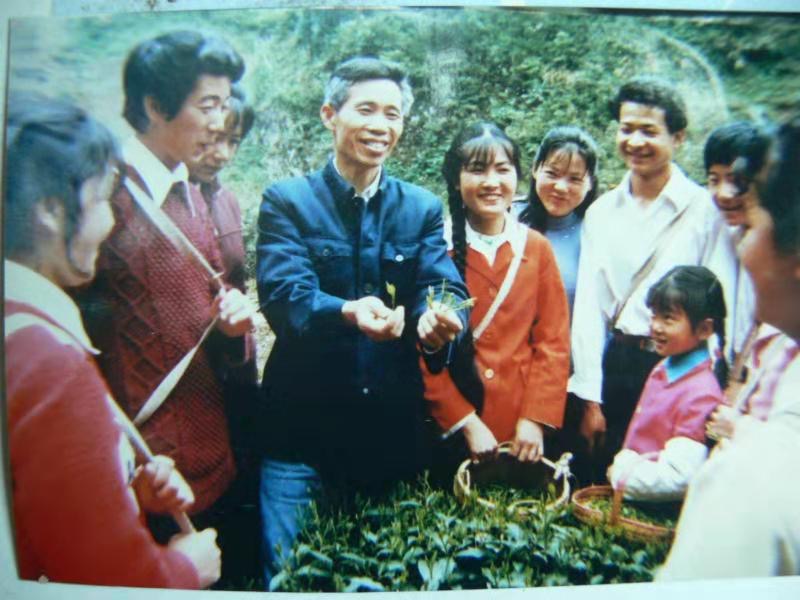

Wang Fangsheng had been learning tea culture and methods of tea production handed down from his father since he was very young. They worked very closely together, traveling the countryside to visit and work with tea farmers to share knowledge and teach skills for producing better quality teas. He helped farmers increase the value of their teas with better garden management and tea processing strategies, such as the avoidance of pesticides and improved frying techniques. As an education on good technique is critical to producing good tea, he helped increase farmer earnings by 900% with this training. He often functioned as a go-between for countryside farmers, selling their tea in the city.

Mr. Wang senior spent decades working for the government after studying tea at university. After inventing the blooming tea, he began visiting the countryside in different provinces to teach over 300 classes training people how to make them, educating over 50,000 people. The technique has since spread to 300 cities in 6 provinces, including Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang. Mr. Wang received special commendation from the government for his contributions to the tea industry, as well as 56 domestic and international awards.

As his own father once did, Wang Fangsheng mentored his son in the trade of making tea. Born in 1972, Wang Huizhou is a sixth generation tea maker in the Wang family. He has already designed 12 blooming teas of his own, and has every intent of continuing his father’s good relationships with local tea farmers. We’re proud to bring you excellent tea from this talented, generous and resilient family.