White tea has become very popular in recent times because of the intensive marketing done in the West in relationship to its health enhancing qualities. White tea appears everywhere in products that range from ready to drink (RTD) beverages to cosmetics. While there has not been as much research with white tea as there has been with green tea, in China it was first used as medicine in Northern Fujian for its effectiveness in treating diseases that inflamed the skin, like Chicken Pox and Measles. White tea never really made it as a domestically popular tea in China. The large buds of the Da Bai Hao bush had primarily been used for green tea in the domestic market, but never commanded the premium prices fetched by the smaller more delicate green tea buds being produced in the provinces to the north. The production has been very ramped up in the last ten years in Northern Fujian replacing the black tea that had been Fujian’s chief export crop, so much so that it is hard to find the Fujian black tea on which the Fujian economy had relied on for centuries.

The confusing history of white tea

There has been a lot of confusion about ‘white tea’ and its origin. In the west, the confusion began with John Blofeld’s book “The Chinese Art of Tea.” Blofeld, who had never come across a white tea, said that it was rare and highly prized and had been more common during the Song Dynasty. He thought that there may have been some at the time in Fujian, but he had not tasted any. The Song reference he cites is from the Da Guan Cha Lun written by the Song emperor Song Hui Zhong Zao Jie. This emperor loved what he named “Bai Cha” which means “white tea”, but was really green tea, which was the only kind of tea that was produced at that time. He named it not for the characteristics of the leaf, but because the tea liquid was the color of white jade, a very light shade of green. This tea was rare at the time, and he made no reference to the area where it had been produced, though tea scholars feel that it had come from Anji in Northern Zhejiang province. During the time that Blofeld was writing his book a Bai Cha bush was discovered by researchers there. From that single bush the current crop of Anji Bai Cha has been propagated.

The real white tea growing area, Jian Yang, Fuding, and Zheng He counties in the north east quarter of Fujian province, was well known a thousand years ago. This area, which during the time of the Song Dynasty from around 1121 to 1125 until 1297 provides tribute tea and was named Beiyuan Gong Cha. All of northern Fujian was called Beiyuan Gong Cha Qu, meaning the production area for tribute tea. This also included Wuyi Shan. At this time, all tea produced in China was in the form of a cake and was green tea. In 1297 the north was further divided into Wuyi Gongcha Qu, making the Wuyi Mountains more important. Of course this all changed in the Ming Dynasty when Ming Hong Wu was declared in 1392 and cake tea was outlawed in China. The tea cakes had become the source of monetary instability and corruption. For almost 150 years tea production was destroyed as Fujian tried to adjust to the new law. Some loose leaf techniques were learned from the Huang Shan area of Anhui, but were difficult to master, which lead to the profusion of varieties that evolved in the northern Fujian area which included black(red) tea, oolong tea, and white tea, white tea coming last.

The Tai Mu Niang Niang myth and the origin of white tea

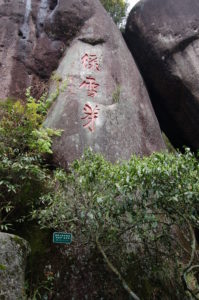

As with most Chinese tea there are myths about the origins of white tea. The most prevalent is the myth of the Tai Mu Niang Niang. (Niang Niang is a name for mother and is commonly used talking about the Guan Yin). The story is that the Tai Mu Niang Niang lived in a cave on Tai Mu Shan (mountain) and discovered the original Da Bai Hao bush on Tai Mu Shan. She used the tea from this plant to cure the fevers of the local children that were dying of a disease that was similar to measles or chicken pox. This was said to take place around 1292 and the tea at that time was called Lu Xue Cha, which means green tea from immortals. Another story involves a man named Chen Minghuan who was lead to the bush by a vision of the Tai Mu Niang Niang. It is interesting the similarity to these myths and the myths about the origins of Tie Guan Yin in Southern Fujian. This female immortal or goddess is fabled for relieving suffering, both from disease and poverty, both of which were and are prevalent in Fujian province.

Harvesting and making white tea

There are two distinct bushes used for white tea production, one from Zheng He county and one from Fuding County, formally named Zheng He Da Bai and Fuding Da Bai, respectively. The Zheng He tea bush can be very large, from three to 5 meters high. The buds are smaller than the Fuding Da Bai and the leaves are yellowish green. This bush produces buds later in the spring and can be processed as green tea, black tea, as well as white tea made from this bush. The Fuding Da Bai bush produces bigger, fatter, longer buds that are thick with hair. This bush has been heavily promoted by the government and is currently being grown in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Jiangxi provinces, and is spreading across China. In those areas the tea produced is green rather than white because the buds early in the season are a good producer for Ming Xian green tea, tea that is harvested before Chinese season of Qing Ming in early April. This tea brings the highest prices in green tea for the year.

On the technique and processing of white tea

The technique of white tea production is not very old. Not until somewhere between 1772 and 1782 was true white tea produced. The process was developed by the Xiao family in Jiang Yang County in northern Fujian and the technique quickly spread to Fuding, Zheng He and Song Xi. The Xiao family wanted to establish a tea making process that would be more economical. They eliminated pan frying and shaping and minimized roasting. Still, not until the early nineteenth century did the evolution of the Da Bai Hao bush produce enough buds to make Bai Hao Yin Shen (Silver Needle) as its own distinct tea.

One of the big differences between green and white tea is how the tea is processed. To make white tea the pickers pick the bud and the leaf together and then separate it into the four general grades creating the three types of white tea, Bai Hao Yin Shen (Silver Needle), Bai Mu Dan(White Peony), Shou Mei, and Gong Mei. Unlike green tea production which is exposed to relatively high temperatures to remove moisture, white tea is dried naturally using sunlight or lower temperatures in doors helping to preserve tea polyphenols. The preferred method is drying by the sun which occurs very quickly. It is not often however that there is enough sunshine to provide this function. Conversely, it takes about forty hours of careful monitoring to dry at low temperatures in doors.

The tea after being withered in covered open sheds, is placed on bamboo racks inside of rooms that are radiator heated at about 40 C. It is important to note the care that Bai Hao Yin Zhen is given when laying the buds on the racks, as if they were solders in formation, neatly lined and properly spaced. The room is well ventilated to remove the humidity with fans. During this natural drying white tea will naturally oxidize very slightly. A master’s skill is shown in temperature control though the drying process. The master makes considerations for ambient temperatures during this slow process and pays meticulous attention to how thick the leaves are piled on the bamboo drying trays. The final stage is a slight roasting, in past times this was done by charcoal, but most tea is now roasted using electrical heating elements.

Marketing misnomers

Because white tea has recently achieved massive popularity in the west for its purported health benefits, tea producers from as far away as India are drying tea naturally and calling it “white tea.” This is incorrect. Even Puer tea leaves are dried in the sun as its first step in production making the buds very white, but this is not considered white tea. By the traditional definition, true white tea can only be made from the Da Bai Hao bushes. Remember that while the leaves from the Da Bai Hao bush can be processed to make both green and white tea, no other tea bush leaves can be used to make true white tea.

White tea health benefits

Like green and yellow tea, white tea is considered cooling in Chinese Medicine. Silver Needle in particular is considered a very effective cooling tea and used to treat inflammation, dental problems, fevers, and skin problems. It is common for countryside Chinese to age Silver Needle (4-6 years) just for its medicinal function. We also know from Western medicine that one of the health benefits of white tea is its high concentration of antioxidants.

How to brew white tea

Overall, white tea has a delicate appearance and delightful gentle aroma. It yields a pleasant, mellow taste that is both subtle and sweet. While it can be brewed with boiling water without damage, it is better to brew at cooler temperatures, between 180-200 degrees Fahrenheit (80 to 90 degrees Centigrade).

Judging a white tea’s quality

Although all white tea is made by the same process and using leaves the same cultivars of tea bushes, different standards of picking from these bushes are divided into four commercially distinct teas:

- Bai Hao Yin Zhen (Silver Needle)

- Bai Mu Dan (White Peony)

- Shou Mei (Longevity Eyebrow)

- Gong Mei (Tribute Eyebrow)

Bai Hao Yin Shen (Silver Needle), the highest grade of white tea, is harvested in the spring and should have long, fat, hairy buds (the hair visible over all sides of the bud), that when infused will turn green. The smell of the dry buds will have a fresh fragrance that becomes slightly floral when brewed. Thin, short leaves that impart a yellowish color when brewed indicate a lower quality white tea.

A good quality Bai Mu Dan (White Peony) will have a picking standard of two leaves to one bud. The longer and plumper the bud indicates it was harvested in the early part of the season. The leaves should be largely unbroken with hair being visible on the underside of the leaf.

While some buds and green leaves are evident with Shou Mei (Longevity Eyebrow), it is mostly broken tea with an overall brownish color.

The ironically named lowest grade of white tea, Gong Mei (Tribute Eyebrow), is mostly brown broken leaves with very few buds. This is a common white tea found in Southern Chinese restaurants.